The human nervous system consists of two main parts, the central nervous system (CNS) and the peripheral nervous system (PNS). The CNS contains the brain and spinal cord. The PNS comprises the nerve fibers that connect the CNS to every other part of the body. The PNS includes the motor neurons that are responsible for mediating voluntary movement. The PNS also includes the autonomic nervous system which encompasses the sympathetic nervous system, the parasympathetic nervous system, and the enteric nervous system. The sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems are tasked with the regulation of all involuntary activities. The enteric nervous system is unique in that it represents a semi-independent part of the nervous system whose function is to control processes specific to the gastrointestinal system. The nervous systems of the body are composed of two primary types of cell: the neurons that carry the chemical signals of nerve transmission, and the glial cells that serve to support and protect the neurons.

Two important concepts relate to the functioning of the nervous system. These terms are efferent and afferent. Efferent connections in the nervous system refer to those that send signals from the CNS to the effector cells of the body such as muscles and glands. Efferent nerves are, therefore, also referred to as motor neurons. Afferent connections refer to those that send signals from sense organs to the CNS. For this reason these nerves are commonly referred to as sensory neurons.

Another important cellular structure in nervous systems are the ganglia. The term ganglion refers to a bundle (mass) of nerve cell bodies. In the context of the nervous system, ganglia are composed of soma (cell bodies) and dendritic structures. The dendritic trees of most ganglia are interconnected to other dendritic trees resulting in the formation of a plexus. In the human nervous system there are two main groups of ganglia. The dorsal root ganglia, which is also referred to as the spinal ganglia, contains the cell bodies of the sensory nerves. The autonomic ganglia contain the cell bodies of the nerves of the autonomic nervous system. Nerves that project from the CNS to autonomic ganglia are referred to as preganglionic nerves (or fibers). Conversely, nerves projecting from ganglia to effector organs are referred to as postganglionic nerves (or fibers). Generally the term ganglion relates to the peripheral nervous system. However, the term basal ganglia (also basal nuclei) is used commonly to describe the neuroanatomical region of the brain that connects the hypothalamus, cerebral cortex, and the brainstem.

Neurons are the highly specialized cells of all nervous systems (e.g. CNS and PNS) that are tasked with transmitting signals from one location to another. These cells accomplish this role through specialized membrane-to-membrane junctions called synapses. Most neuron possess an axon which is a long protrusion from the body (soma) of the neuron to the synapse. Axons can extend to distant parts of the body and make thousands of synaptic contacts such as is the case with the CNS neurons of the spinal cord. Axons frequently travel through the body in bundles called nerves. The synapses are termed pre-synaptic and post-synaptic. The pre-synaptic synapse will release secretory granule contents in response to the propagation of an electrochemical signal (action potential) down its axon. The released substance (termed a neurotransmitter) will then, most likely, bind to a specific receptor on the membrane of the post-synaptic synapse, thereby, propagating the initial action potential to the next neuron. The human nervous system is composed of hundreds of different types of neurons. These include sensory neurons that transmute physical stimuli such as light and sound into neural signals, and motor neurons that are responsible for converting neural signals into activation of muscles or glands.

Glial cells (named from the Greek for “glue”) are the specialized non-neuronal cells of the nervous system that provide protection, support and nutrition for neurons. As the Greek name glue infers, glial cells hold neurons in place and provide guidance cues which directs axons of the neurons to their appropriate target cell(s). Glial cells are responsible for the maintenance of neural homeostasis, for the formation of myelin, and they play a participatory role in signal transmission in the nervous system. Glial cells provide an electrical insulation (myelin) for neurons which allows for rapid transmission of action potentials and also prevents the abnormal propagation of nerve impulses to inappropriate neurons. The glial cells that produce the myelin sheath are called oligodendrocytes in the CNS and Schwann cells in the PNS. Glial cells also destroy pathogens and remove dead neurons.

The sympathetic nervous system (SNS) is predominantly responsible for excitatory action potentials with the goal of inducing the “fight-or-flight” responses of the body under conditions of stress. In general, activation of the SNS results in contraction, for example, vasoconstriction. Although stress is a major trigger of the SNS, it is constantly active at a basal level to maintain homeostasis. The activation of the neurons of the SNS occurs as a result of signals arising in the region of the brain stem called the nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS, for the Latin term nucleus tractus solitarii). The NTS receives a wide range of sensory inputs from both systemic and central baroreceptors and chemoreceptors.

The neurons of the SNS emanate from the medulla, specifically the rostral ventrolateral medulla (RVLM), and travel down the spinal cord where they synapse with short preganglionic neurons within the sympathetic ganglia. The ganglia of the SNS are the nerve cell bodies that lie on either side of the spinal cord. Preganglionic sympathetic fibers are those that exit the spinal cord synapses within these ganglia. The preganglionic neurotransmitter is acetylcholine, ACh. ACh released from the sympathetic preganglionic neuron binds to nicotinic ACh receptors (nAChR) on the postganglionic neuron. ACh binding depolarizes the cell body of the postganglionic neuron generating an action potential that travels to the target organ to elicit a response. The neurotransmitter released from sympathetic postganglionic neurons is norepinephrine which binds to its receptor expressed in the target cell.

The target organ receptors responsive to signals from the SNS are those of the adrenergic family, specifically α1, α2, β1, and β2 (see below). Although the primary neurotransmitter released from sympathetic postganglionic neurons is norepinephrine, there are two important exceptions. These exceptions are the postganglionic neurons that innervate chromaffin cells of the adrenal medulla and those that innervate the sweat glands. When the postganglionic neurons that innervate sweat glands are activated, they release ACh (not epinephrine) which binds to muscarinic ACh receptors (mAChR: specifically the M1 and M3 receptors) on the target cell. Adrenal medullary chromaffin cells are functionally analogous to sympathetic postganglionic neurons and when stimulated by ACh from a sympathetic preganglionic neuron these cells release epinephrine and norepinephrine into the circulation. The receptors triggering the release of adrenal epinephrine and norepinephrine are nicotinic (nAChR).

The parasympathetic nervous system is predominantly responsible for inhibitory action potentials resulting in relaxation, for example, vasodilation. The parasympathetic nervous system is responsible for stimulation of “rest-and-digest” and “feed-and-breed” activities that occur when the body is at rest. These responses include, but are not limited to, sexual arousal, salivation, lacrimation (tears), urination, digestion, and defecation.

Within the head the parasympathetic nervous system includes cranial nerves III, VII, and IX, while cranial nerve X (comprising the vagus nerves) exits the brain stem to innervate the organs of the body. Like the SNS, the activation of the vagus nerves of the parasympathetic nervous system occurs as a result of signals arising in the NTS. There are three nuclei within the medulla that send out vagal nerves of the parasympathetic nervous system. These nuclei are the dorsal motor nucleus, the solitary nucleus, and the nucleus ambiguus (located in the reticular formation in the medulla oblongata).

Parasympathetic neural outputs to the heart arise primarily within the nucleus ambiguus. The ganglia of the parasympathetic nervous system are also referred to as terminal ganglia as they lie close to, or within, the organs that they innervate. The exceptions to this are the parasympathetic ganglia of the head and neck. Parasympathetic ganglia are those that are found within the target organ. Preganglionic parasympathetic fibers associated with the vagal nerve all exit the brain stem, they do not travel down the spinal chord except for the pelvic splanchnic nerves which exit the spinal cord in the S2-S4 region.

The parasympathetic preganglionic nerves enter their target organs where they form synapses with postganglionic neurons. Like the sympathetic ganglia, the neurotransmitter of parasympathetic preganglionic nerves is ACh. When released from these nerves the ACh binds to nicotinic ACh receptors (nAChR) on the postganglionic nerve. However, unlike sympathetic postganglionic nerves, activation of the parasympathetic postganglionic nerves results in the release of ACh. When released from the parasympathetic postganglionic neuron, the ACh binds to muscarinic ACh receptors (mAChR) in the target cells, primarily the M2 and M3 receptors.

Within the cardiovascular system the norepinephrine released from sympathetic postganglionic neurons binds to β1 (and to a lesser extent β2) adrenergic receptors expressed on cardiac myocytes of the heart within the sinoatrial (SA) node (primary cardiac pacemaker cells), the atrioventricular (AV) node, the ventricles, and the Purkinje fibers of the cardiac conduction system. Activation of the β1 receptor in the heart results in increased force of contraction (inotropy), increased heart rate (chronotropy), and increased cardiac conductance (dromotropy). These effects are exerted as a result of the increased levels of cAMP and the activation of PKA that result from β1 receptor activation of Gs-type G-proteins.

Activation of the β1 receptor associated Gs-type G-proteins results in the consequent activation of adenylate cyclases. The major adenylate cyclases activated by β-adrenergic receptors in the heart are encoded by the ADCY5 and ADCY6 genes. The ADCY5 encoded enzyme, identified as AC5, is localized to the nuclear membrane and to specialized domains of the membranes of the T-tubule system of the cardiac myocyte. AC5 activity is regulated by both β1– and β2-adrenergic receptors in cardiac myocytes. The ADCY6 encoded enzyme, identified as AC6, is localized to the sarcolemma (muscle cell plasma membrane) of the cardiac myocyte outside the T-tubule system. AC6 activity is regulated exclusively by β1-adrenergic receptors.

The extent to which cAMP can exert its effects, either directly or through the activation of PKA, is controlled by the receptor-mediated activation of the various adenylate cyclases as well as by the activities of various enzymes of the phosphodiesterase (PDE) family. Multiple PDE isoforms are expressed within various tissues of the heart, however, within the cardiac myocyte the predominate PDE are members of the PDE4D family, specifically the PDE4D5 and PDE4D8 isoforms. However, it should be noted that members of the PDE2 and PDE3 families are also expressed within cardiac myocytes. The PDE4D8 isoform is localized to protein complexes at the sarcolemma (plasma membrane) that includes the β1-adrenergic receptor.

Numerous responses, exerted by β-adrenergic receptor activation, are the result of cAMP itself. Direct effects of cAMP within cardiac myocytes of the SA node, AV node, and the Purkinje fibers contribute to positive chronotropic and dromotropic effects elicited as a result of β1-adrenergic receptor activation. The effects of direct cAMP action include binding to, and enhancing of the activation of, the hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-gated channel 2 and 4 (HCN2 and HCN4) that are responsible for the pacemaker current (If or IKf) in cardiac nodal cells. The HCN channels are often referred to as funny current channels. The resulting cAMP-mediated activation increases the pacemaker current leading to positive chronotropic and dromotropic activities of the cardiac myocytes.

Another important protein activated by direct interaction with cAMP is RAP guanine nucleotide exchange factor 3 (encoded by the RAPGEF3 gene). The RAPGEF3 encoded protein was originally, and is commonly, referred to as exchange protein directly activated by cAMP, EPAC (also known as EPAC1). The activation of EPAC by cAMP results in the activation of Ca 2+ /calmodulin kinase II (CaMKII or CaMK2).

Humans express 11 genes in the Ca 2+ /calmodulin-dependent protein kinase family. Four of these genes encode CaMKII enzymes. The four CaMKII encoding genes are identified as CAMK2A, CAMK2B, CAMK2D, and CAMK2G genes. These genes encode the CaMKIIα, CaMKIIβ, CaMKIIδ, and CaMKIIγ isoforms, respectively. CaMKIIα and CaMKIIβ are primarily found in nervous tissues while CaMKIIδ and CaMKIIγ are found at low levels in virtually all tissues. The different CaMKII isoforms can interact to form various heteromeric holoenzymes such that at least 28 different holoenzyme forms have been identified. These different holoenzymes have differing affinities for calmodulin. Most CaMKII holoenzymes are dodecameric consisting of two hexameric rings of subunits.

When activated, CaMK2 phosphorylates the calcium release channel, ryanodine receptor 2, RYR2, resulting in increased release of Ca 2+ stored within the sarcoplasmic reticulum, SR. Increased free intracellular Ca 2+ plays a major role in the contractile activity of muscle cells through, among other effects, the activation of the calmodulin subunit of myosin light chain kinases. Thus, the stimulated release of Ca 2+ from the SR contributes to the increased inotropic and chronotropic effects of β1-adrenergic receptor activation.

Activation of EPAC also results in the downregulation of the regulatory subunit of voltage-gated potassium channels which are commonly identified as Kv channels. The regulatory subunit of the Kv channels is encoded by the KCNE1 gene and is commonly referred to as the β-subunit. The specific cardiac Kv family channels that are regulated by the KCNE1 encoded protein are Kv2.1 channels encoded by the KCNB1 gene and Kv1.9 channels encoded by the KCNQ1 gene. The KCNQ1 encoded potassium channels are required for the repolarization phase of cardiac myocyte action potentials. The KCNQ1 (Kv1.9) channels constitute the cardiac K + current identified as IKs where the I refers to inward current and the Ks refers to slow acting outwardly rectifying K + transport.

Within the cardiac myocyte PKA is localized to specific subcellular locations through its anchoring to proteins of the A-kinase anchoring protein (AKAP) family. Upon its activation via cAMP, PKA mediates its effects on cardiac contractility and chronotropy via the phosphorylation of numerous proteins controlling these processes. PKA phosphorylates L-type Ca 2+ channels in the plasma membrane (sarcolemma) and RYR2 in the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR).

The PKA-mediated phosphorylation of plasma membrane L-type Ca 2+ channels results in increased influx of Ca 2+ and the phosphorylation of the RYR2 channel results in increase release of Ca 2+ stored in the SR. Both of these events lead to increased Ca 2+ availability for activation of the calmodulin subunit of myosin light-chain kinase, MLCK. It is important to note that the effects of PKA in the striated muscle cells of the heart are distinct from the effects of PKA in smooth muscle cells. Whereas, in striated cardiomyocytes the effect of PKA is increased contractile activity, in smooth muscle the phosphorylation of the plasma membrane calcium channels leads to inhibition and PKA phosphorylates the smooth muscle MLCK isoform rendering it less active. The net effect in smooth muscle is relaxation, not contraction.

The released Ca 2+ also interacts with troponin C (TnC) resulting a conformational change to the troponin complex (troponin C, I, and T) that moves the attached tropomyosin away from the myosin binding sites on actin. This conformational change abolishes the inhibitory action of the TnI protein of the complex. In addition, the conformational change permits nearby myosin heads to interact with myosin binding sites, and contractile activity ensues. PKA also phosphorylates troponin I preventing it from inhibiting the interactions of actin and myosin.

Another important target of PKA is the protein identified as phospholamban (PLN). Phospholamban interacts with SR membrane-associated Ca 2+ reuptake channels identified as sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca 2+ -ATPases (SERCA: encoded by ATP2A family genes). The cardiac myocyte SERCA is identified as SERCA2A and is encoded by the ATP2A2 gene. The normal function of PLN is to inhibit the reuptake of Ca 2+ into the SR via the action of SERCA2A transporters. Phosphorylation of PLN by PKA reduces the inhibitory action of PLN on SERCA2A promoting Ca 2+ reuptake. Diastolic relaxation of cardiac myocytes requires Ca 2+ reuptake by the SR, thus, the inhibition of PLN allows for an increased rate of myocyte contraction and relaxation resulting in an overall increased force of contraction.

Within the large coronary arteries (predominantly the left and right coronary arteries, LCA and RCA, respectively) sympathetic postganglionic nerve release of norepinephrine results in activation of the α1 (and to a lessor extent α2) adrenergic receptors in the smooth muscle cells resulting in vasoconstriction. This vasoconstriction of the large coronary arteries, which are branches of the aorta, allow a greater volume of blood to remain in the aorta for delivery of oxygen- and nutrient-rich blood to the tissues during sympathetic activation such as is typified by the fight-or-flight response.

However, the heart muscle cannot be starved of blood and this is prevented by the presence of high concentrations of β1-adrenergic receptors on the smooth muscle cells of the small coronary arteries. The activation of these β1 receptors results in vasodilation of the small coronary arteries. Within the periphery, the smooth muscle cells of the vessels in skeletal muscle also possess β-adrenergic receptors, predominantly the β2 class. Stimulation of these β2 receptors also results in vasodilation. This effect allows the skeletal muscle vasculature to receive larger volumes of blood during the fight-or-flight response. The primary activator of the β2 adrenergic receptors in skeletal muscle vasculature is the epinephrine released from the adrenal medulla in response to sympathetic activation.

Within the cardiovascular system the primary target cells of the heart that receive parasympathetic innervation are the SA node (from the right vagus nerve), the AV node (from the left vagus nerve), and atrial cells. The cardiac muscarinic receptor that binds the ACh released from parasympathetic postganglionic nerves is the M2 type receptor. Each of the muscarinic ACh receptors is a GPCR and the M2 receptors are coupled to a Gi-type G-protein. Activation of the M2 receptor results in decreased levels of cAMP leading to reduced direct effects of cAMP and reduced activation of PKA, thereby reducing all of the processes discussed above.

Activation of the M2 receptor also results in the activation of inwardly rectifying K + channels resulting in rapid repolarization of cardiac myocytes leading to termination of an action potential. The particular class of K + channels that are responsive to G-proteins are activated by the βγ subunits of the G-protein. These K + channels are commonly referred to as G protein-coupled inwardly-rectifying potassium channels (GIRK). The GIRK are members of the KCNJ subfamily of voltage-gated K + channels. The specific cardiac GIRK channels are heterodimers formed from the proteins encoded by the KCNJ3 and KCNJ5 genes. These proteins are commonly identified as Kir3.1 and Kir3.4. This cardiac nodal cell potassium channel constitutes the IKACh current that is responsible for phase 4 of nodal cell action potentials.

The net effect of parasympathetic activation of nodal M2 receptors is decreased heart rate (chronotropy) and decreased cardiac conductance (dromotropy). The effects of the parasympathetic nervous system on the heart supersede the effects of the sympathetic nervous system such that even in the face of sympathetic stimulation, parasympathetic stimulation can depress cardiac activity.

Within the vasculature ACh binds to the M3 receptor on endothelial cells leading to increased NO production resulting in vasodilation. However, this ACh is not derived from parasympathetic nerves but directly from the circulation. Parasympathetic postganglionic ACh does stimulate M3 receptor-mediated NO production but this is only seen in the external genitalia.

Neurotransmitters are endogenous substances that act as chemical messengers by transmitting signals from a neuron to a target cell across a synapse. Prior to their release into the synaptic cleft, neurotransmitters are stored in secretory vesicles (called synaptic vesicles) near the plasma membrane of the axon terminal. The release of the neurotransmitter occurs most often in response to the arrival of an action potential at the synapse. When released, the neurotransmitter crosses the synaptic gap and binds to specific receptors in the membrane of the post-synaptic neuron or cell.

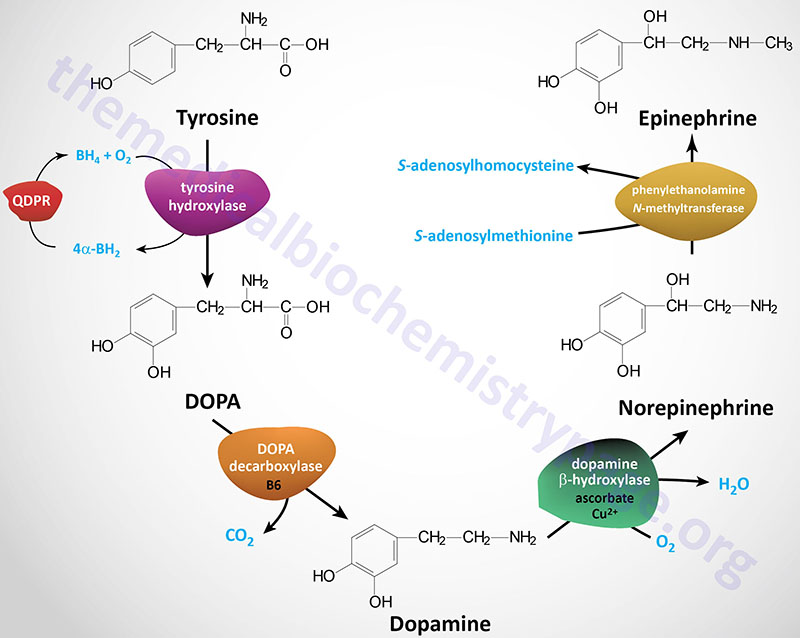

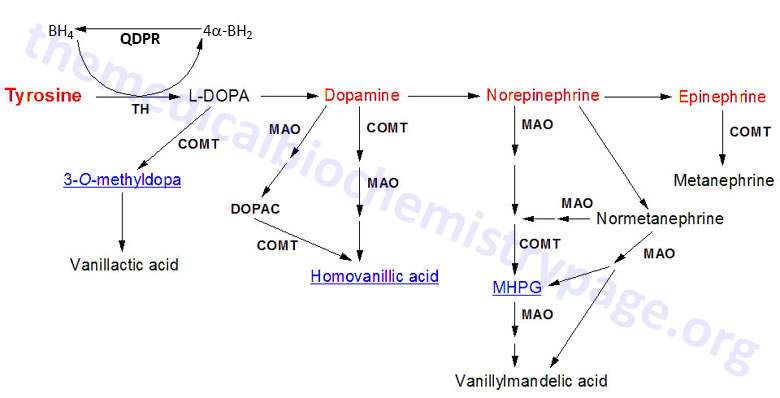

Neurotransmitters are generally classified into two main categories related to their overall activity, excitatory or inhibitory. Excitatory neurotransmitters exert excitatory effects on the neuron, thereby, increasing the likelihood that the neuron will fire an action potential. Major excitatory neurotransmitters include glutamate, epinephrine and norepinephrine. Inhibitory neurotransmitters exert inhibitory effects on the neuron, thereby, decreasing the likelihood that the neuron will fire an action potential. Major inhibitory neurotransmitters include GABA, glycine, and serotonin. Some neurotransmitters, can exert both excitatory and inhibitory effects depending upon the type of receptors that are present.

In addition to excitation or inhibition, neurotransmitters can be broadly categorized into two groups defined as small molecule neurotransmitters or peptide neurotransmitters. Many peptides that exhibit neurotransmitter activity also possess hormonal activity since some cells that produce the peptide secrete it into the blood where it then can act on distant cells. Small molecule neurotransmitters include (but are not limited to) acetylcholine, GABA, amino acid neurotransmitters, ATP and nitric oxide (NO). The peptide neurotransmitters include more than 50 different peptides. Many of the gut-derived and hypothalamic neurotransmitter peptides are discussed in detail in the Gut-Brain Interrelationships page. Several peptide neurotransmitters are all derived from the same precursor protein, pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC), as discussed in the Peptide Hormones page.

Many neurotransmitters can also be divided into two broad categories dependent upon whether the receptor activated by the binding of transmitter is a metabotropic or an ionotropic receptor. Metabotropic receptors activate signal transduction upon transmitter binding similar to many peptide hormone receptors which involves a second messenger. Metabotropic receptors are members of the G-protein coupled receptor (GPCR) family. Ionotropic receptors ligand-gated ion channels. Some neurotransmitters, for example glutamate and acetylcholine, bind to multiple receptors some of which are metabotropic and some of which are ionotropic.

The transmission of an efferent signal from the CNS to a target tissue, or an afferent signal from a peripheral tissue back to the CNS occurs as a result of the propagation of action potentials along a nerve cell. Nerve cells are excitable cells and they can respond to various stimuli such as electrical, chemical, or mechanical. When the excitation event is propagated along the nerve cell membrane it is referred to as a nerve impulse or more often as an action potential. When a nerve cell terminates on another it does so at a specialized structure called a synapse. Synaptic transmission refers to the propagation of nerve impulses (action potentials) from one nerve cell to another. The synapse is a junction at which the axon of the presynaptic neuron terminates at some location upon the postsynaptic neuron. The end of a presynaptic axon, where it is juxtaposed to the postsynaptic neuron, is enlarged and forms a structure known as the terminal button (pronounced “boo-tawn”). An axon can make contact anywhere along the second neuron: on the dendrites (an axodendritic synapse), the cell body (an axosomatic synapse) or the axons (an axoaxonal synapse).

Action potentials are the result of membrane depolarization which is brought about by a change in the distribution of ions across the membrane. Differences in ion concentrations on either side of a membrane result in a electrical charge differential across the membrane which is referred to as an electrochemical potential. Changes in ion concentrations on either side of a membrane result in depolarization of the membrane. Once a portion of a membrane is depolarized, the ion gradients need to be returned to the “resting” state, a process referred to as repolarization. The movement of ions across the membrane is the function of proteins and protein complexes termed ion channels. Because nerve transmission involves changes in voltage (charge) across the plasma membrane, these ion channels respond to the voltage changes and are, therefore, referred to as voltage-gated ion channels.

The resting membrane potential of a neuron is maintained by the differential distribution of K + and Na + ions. The concentration of intracellular K + is much higher than the extracellular concentration. This situation is just the opposite for Na + , which is at a much higher concentration outside the cell than inside. This differential is maintained through the action plasma membrane transporters of the Na + ,K + -ATPase family. The initiation and propagation of an action potential is the result of the opening and closing of voltage-gated K + channels and voltage-gated Na + channels. In the rested stated both types of voltage-gated channels are closed. In response to a depolarizing signal (an excitation signal) the fast acting voltage-gated Na + channels open allowing an influx of Na + ions into the cell. The influx of Na + causes more voltage-gated Na + channels to open propagating the depolarization event. The Na + channels ultimately close (within milliseconds) to an inactivated state, meaning they cannot be re-opened prior to the membrane returning to its initial rested state.

The opening of voltage-gated K + channels occurs much slower than for the Na + channels and they are not fully open until the Na + channels have re-closed. The opening of the K + channels allows K + to exit the cell which brings the net charge inside the cell back to the rested state potential. The opening of the K + channels, following closure of the Na + channels, represents the repolarization stage and brings the action potential to an end.

Nerve impulses are transmitted from one neuron to another, or from a neuron to a target tissue cell, at synapses by the release of neurotransmitters. As discussed in detail throughout this page, neurotransmitters can be small chemicals, such as amino acids or amino acid derivatives, or they can be lipids, such as the endocannabinoid, anandamide. As a nerve impulse, or action potential, reaches the end of a presynaptic axon, molecules of neurotransmitter are released into the synaptic space. The release of neurotransmitter involves the processes of exocytosis. When an action potential reaches the presynaptic terminal the membrane depolarization results in the opening of voltage-gated Ca 2+ channels. The influx of Ca 2+ ions induces the membranes of neurotransmitter secretory vesicles to fuse with the plasma membrane allowing the contents to be released into the synaptic cleft.

In order to move a skeletal muscle cell, an action potential must be initiated from a peripheral motor neuron. Cardiac muscle (myocardial) cells on the other hand, can initiate their own electrical activity in the absence of an autonomic nerve-mediated action potential. With respect to skeletal muscle, nerve transmission occurs when an axon of a post-ganglionic nerve terminates on a skeletal muscle fiber, at specialized structures called the neuromuscular junction. An action potential occurring at this site is known as neuromuscular transmission. At a neuromuscular junction, the axon subdivides and branches into numerous structures, referred to as terminal buttons (pronounced “boo-tawns”) or end bulbs, that can then innervate numerous skeletal muscle fibers. The result is that many muscle fibers can be innervated by a single neuron instead of each fiber having to be dependent upon an individual neuron for contractile activation.

The skeletal muscle fibers that are innervated by branches from the same neuron constitute a motor unit. Large muscles in the body (e.g. the gastrocnemius) contain numerous motor units. This arrangement of the motor units in a particular muscle allows for activation of only a specific part of a muscle at any given time. This represents a form of spatial control over muscle fiber contraction within a muscle, a feature not associated with cardiac muscle excitation as discussed below.

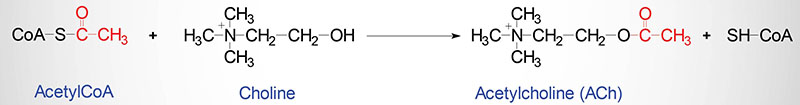

The terminal buttons (end bulbs) of the motor neurons reside within depressions formed in the skeletal muscle plasma membrane (sarcolemma). At these locations the skeletal muscle membrane is thickened and is referred to as the motor end plate. The space between the terminal buttons (end bulbs) and the motor end plate is similar to the synaptic cleft that exists where the pre-synaptic and post-synaptic membranes of neurons are in close proximity. The particular neurotransmitter in use at the neuromuscular junction is acetylcholine, ACh.

When an action potential reaches the pre-synaptic membrane of a motor neuron the permeability of the membrane changes. This change in permeability allows Ca 2+ to enter the nerve endings triggering exocytosis of ACh. The released ACh then binds to nicotinic ACh receptors (nAChR) that are concentrated in the motor end plate membrane. Once released from the motor neuron, the level of active ACh is controlled by its catabolism through the action of acetylcholinesterase. As discussed below, nAChR are members of the ionotropic receptor superfamily (ion channel receptors). Activation of nicotinic ACh receptors in the motor end plate results in an increase in Na + and K + conductance through the nAChR channel.

The resulting influx of Na + into the skeletal muscle cell produces a depolarizing potential. As a result of this depolarization, action potentials are conducted in both directions, away from the motor end plate, along the muscle fiber. These action potentials are the result of the initial membrane depolarization and propagated across the surface membrane via the opening of voltage-gated Na + channels. The action potential is then propagated down the T-tubule system which directly interacts with the sarcoplasmic reticulum, SR. Activation of the SR leads to the release, into the sarcoplasm (cytoplasm of muscle cells), of stored Ca 2+ through the opening of Ca 2+ release channels. The SR calcium release channels are also known as the ryanodine receptor (RYR) due to the fact that they were originally identified by their high affinity for the plant alkaloid ryanodine. The end result of the ACh-initiated propagating action potential is muscle contraction.

A particularly devastating disease that results from defects in the overall processes of neuromuscular nerve transmission is myasthenia gravis, MG. MG is a very serious disorder that is often times fatal. The characteristic features of the disease are weakened skeletal muscles that tire with very little exertion. MG is an auto-immune disease associated with antibodies to the nAChR of the neuromuscular junction. Binding of the antibodies to the receptor results in receptor destruction as well as receptor cross-linking. In most patients with MG there is a 70%–90% reduction in motor end plate nicotinic receptor number. Two major forms of MG exist, one in which the extraocular muscles are the ones primarily affected and in the other form there is a generalized skeletal muscle involvement. In the latter form of MG, the muscles of the diaphragm become affected resulting in respiratory failure which contributes to the mortality of MG. Treatment of MG involves numerous approaches including the use of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors. The use of these types of drugs allows for enhanced levels of ACh at the motor end plate during repeated muscle stimulation.

Once the molecules of neurotransmitter are released from a cell as the result of the firing of an action potential, they bind to specific receptors on the surface of the postsynaptic cell. In all cases in which these receptors have been cloned and characterized in detail, it has been shown that there are numerous subtypes of receptor for any given neurotransmitter. As well as being present on the surfaces of postsynaptic neurons, neurotransmitter receptors are found on presynaptic neurons. In general, presynaptic neuron receptors act to inhibit further release of neurotransmitter.

The vast majority of neurotransmitter receptors belong to a class of proteins known as the G-protein coupled receptors, GPCR. The GPCR are also called serpentine receptors because they exhibit a characteristic transmembrane structure: that is, they span the cell membrane, not once but seven times. The link between neurotransmitters and intracellular signaling is carried out by association, either with the receptor-associated G-protein, with protein kinases, or by the receptor itself in the form of a ligand-gated ion channel (for example, the nicotinic acetylcholine receptors). The receptors that are of the GPCR family are referred to as metabotropic receptors, whereas, the ligand-gated ion channel receptors are referred to as ionotropic receptors.

One additional characteristic of neurotransmitter receptors is that they are subject to ligand-induced desensitization. Receptor desensitization refers to the phenomenon whereby upon prolonged exposure to ligand results in uncoupling of the receptor from its signaling cascade. A common means of receptor desensitization involves receptor phosphorylation by receptor-specific kinases. Following phosphorylation of the receptor there is increased affinity for inhibitory molecules that uncouple the interaction of receptor with its associated G-protein. One major class of these desensitizing inhibitors are the arrestins. Arrestins were first identified in studies of β-adrenergic receptor desensitization and so were called β-arrestins.

This Table is a non-inclusive listing of the neurotransmitters

| Transmitter Molecule | Transmitter Class | Derived from | Receptors / Activities / Comments |

| Acetylcholine | Choline | functions in both the CNS and the PNS; receptors are cholinergic; 2 receptor classes: muscarinic (metabotropic) and nicotinic (ionotropic); within the periphery ACh is the major transmitter of the autonomic nervous system where it activates muscles; within the brain its major effects are inhibitory or anti-excitatory; its actions in cardiac tissue are also inhibitory | |

| Adenosine | other | ATP | is an inhibitory neurotransmitter within the CNS, suppresses arousal thus promoting sleep; within the periphery adenosine exerts anti-inflammatory actions, stimulates vasodilation through vascular smooth muscle, induces bronchospasm in the lungs; within the heart it affects the cardiac conduction system; adenosine binds to a family of adenosine receptors (members of GPCR family) identified as A1 (coupled to Gi/o), A2A (coupled to Gs), A2B (coupled to Gs or Gq-dependent upon tissue), and A3 (coupled to Gi or Gq-dependent upon tissue); activation of A1 receptors expressed in cardiac pacemaker cells of sinoatrial node leads to reduced heart rate (chronotropy); activation of A2A receptors in coronary vascular smooth muscle cells induces vasodilation via the actions of the associated Gq; transport of adenosine in and out of cells is the function of the equilibrative nucleoside transporters (ENT) which are encoded by the SLC29 family of genes |

| Anandamide | other | phospholipids via at least two pathways | an endocannabinoid, binds to the cannabinoid receptors (CB1 and CB2) with highest affinity for CB1; CB1 is most abundant receptor in the CNS; classic response to CB1 activation is stimulation of food intake; exerts peripheral effects on overall energy homeostasis |

| Aspartate | amino acid | stimulates the NMDA receptor but not as strongly as glutamate | |

| ATP | other | as a neurotransmitter ATP is released from sympathetic, sensory and enteric nerves; ATP binds to metabotropic G-protein coupled receptors (GPCR) of the P2Y family of purinergic/pyrimidinergic receptors of which there are ten in humans: P2Y1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10–14; P2Y12 is primarily expressed on the surface of platelets where it serves as a major ATP-mediating receptor of blood coagulation |

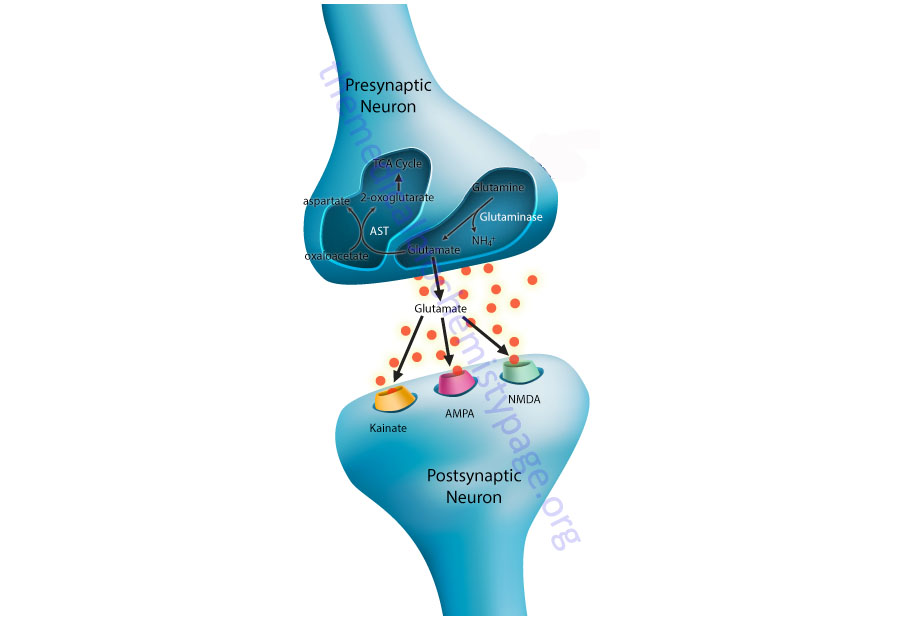

Within the CNS glutamate is the main excitatory neurotransmitter. Neurons that respond to glutamate are referred to as glutamatergic neurons. Postsynaptic glutamatergic neurons possess four distinct classes of ionotropic receptors that bind glutamate released from presynaptic neurons. Three of these ionotropic receptor classes have been identified on the basis of their binding affinities for certain substrates and are thus, referred to as the kainate, 2-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA), N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors. The fourth class of ionotropic glutamate receptor is termed the delta (δ) receptors. Each of these classes of glutamate receptor subunit form ligand-gated ion channels, thus the derivation of the term ionotropic. There are also multiple subtypes of each of these classes of ionotropic glutamate receptor subunits.

Within the CNS glutamatergic neurons are responsible for the mediation of many vital processes such as the encoding of information, the formation and retrieval of memories, spatial recognition and the maintenance of consciousness. Excessive excitation of glutamate receptors has been associated with the pathophysiology of hypoxic injury, hypoglycemia, stroke and epilepsy.

The AMPA receptor subunits are referred to as GluA1 (GluR1) through GluA4 (GluR4) and each is encoded by separate genes. Functional AMPA receptors consist of heterotetramers that are formed from dimers of GluA2 and dimers of either GluA1, GluA3, or GluA4. The GluA2 subunit of the receptor is responsible for regulating the permeability of the channel to calcium ions. The GluA2 mRNA is subject to RNA editing which alters the function of the calcium permeability character of the subunit. For details on the editing of the GluA2 mRNA go to the RNA: Transcription and Processing page. The AMPA receptors are found on most excitatory postsynaptic neurons where they mediate fast excitation. Indeed, AMPA receptors are responsible for the bulk of fast excitatory synaptic transmission throughout the CNS. The concept of fast synaptic transmission relates to the fact that the ion channel opens and closes quickly in response to ligand (e.g. glutamate) binding. The ion permeability of the AMPA receptors is controlled by the GluA2 subunit. AMPA receptors have low permeability to calcium ions even in the ligand-activated state and this is to prevent excitotoxicity in these neurons.

The NMDA receptor is generated from two separate subunit families. These subunit families are identified as GluN1 (also called NMDAR1) and GluN2. There are four GluN2 subunits (GluN2A–GluN2D; also NMDAR2A–NMDAR2D). The four different GluN2 subunits are encoded by distinct genes. Although there is a single gene encoding the GluN1 subunit, multiple isoforms of this subunit are generated through alternative splicing events. The functional NMDA receptor is composed of a heterotetramer with all forms containing the GluN1 subunit and one of the different GluN2 subunits.

Unlike the other ionotropic glutamate receptors, the NMDA receptors are activated by simultaneous binding of glutamate and glycine. Glycine serves as a co-agonist and both amino acid neurotransmitters must bind in order for the receptor to be activated. Glycine binds to the GluN1 subunit while glutamate binds to the GluN2 subunit.

Glutamate binding to NMDA receptors results in calcium influx into the postsynaptic cells leading to the activation of a number of signaling cascades. These signaling cascades can include activation of Ca 2+ /calmodulin-dependent kinase II (CaMKII) leading to phosphorylation of the GluA2 AMPA receptor subunit. This latter effect results in long-term potentiation (LTP).

NMDA receptor activation also triggers PKC-dependent insertion of AMPA receptors into the synaptic membrane during LTP as well as activation of the kinases phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K), protein kinase B/AK strain transforming (PKB/AKT), and glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3), each of which modulates LTP. PKB (protein kinase B)/AKT (AK strain transforming) was originally identified as the tumor inducing gene in the AKT8 retrovirus found in the AKR strain of mice. Humans express three genes in the AKT family identified as AKT1 (PKBα), AKT2 (PKBβ), and AKT3 (PKBγ).

The kainate receptor subunits are known as GluK1 through GluK5 (formerly GluR5, GluR6, GluR7, KA1, and KA2). The GluK1–GluK3 subunits can form hetero- and homomeric receptor complexes. In addition, alternative splicing of the GluK1 and GluK2 mRNAs results in at least five distinct subtypes (GluK1a–GluK1c, GluK2a, GluK2b). Less is known about the physiological significance of the kainate receptors. One major role of the kainate receptors is in the regulation of synaptic plasticity. Another important function of the kainate receptors is in the regulation of the release of the inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA. This function of the kainate receptors is due to their presence on presynaptic GABAergic neurons.

The delta (δ) glutamate receptors were identified as ionotropic glutamate receptors based upon amino acid sequence similarity to the other more well-characterized ionotropic glutamate receptors. However, these proteins do not form glutamate-gated functional ion channels either alone or in combination with any of the other ionotropic glutamate receptor proteins. Indeed, these proteins do not bind glutamate or any other excitatory amino acid receptor ligands. The GluD1 receptor (encoded by the GRID1 gene) is prominently expressed in inner ear hair cells and neurons of the hippocampus. The presentation of GluD1 in the inner ear indicates that it has a role in hearing. The GluD2 receptor (encoded by the GRID2 gene) is expressed exclusively in the Purkinje cells of the cerebellum. GluD2 function is critical for the development of neuronal circuits and functions that includes long-term depression (LTD), learning and memory.

Glutamate can also bind to another class of receptor termed the metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluR; where the small m refers to metabotropic). There are eight known metabotropic glutamate receptors identified as mGluR1–mGluR8. Unlike the ionotropic receptors, the mGluR are members of the G-protein coupled receptor (GPCR) family. The mGluR can be divided into three distinct subclasses based upon sequence similarities and receptor associated G-protein.

Group I mGluR include mGluR1 and mGluR5, both of which are coupled to Gq type G-proteins and upon activation trigger increased production of DAG and IP3. Group II is composed of mGluR2 and mGluR3. Group III is composed of mGluR4, mGluR6, mGluR7, and mGluR8. Both group II and III mGluR activate an associated Gi type G-protein resulting in decreased production of cAMP.

The mGluR are primarily expressed on neurons and glial cells in close proximity to the synaptic cleft. Within the CNS, mGluR modulate the neurotransmitter effects of glutamate as well as a variety of other neurotransmitters. In addition to the CNS, mGluR have a widespread distribution in the periphery. Given their wide pattern of expression, diverse roles for mGluR have been suggested. Some of these processes include control of hormone production in the adrenal gland and pancreas, regulation of mineralization in the developing cartilage, modulation of cytokine production by lymphocytes, directing the state of differentiation in embryonic stem cells, and modulation of secretory functions within the gastrointestinal tract.

| Receptor Name (other names) | Gene Symbol | Type / Class | Functions / Comments |

| mGluR1 | GRM1 | metabotropic, group I family | GPCR coupled to Gq-type G-protein; primarily a post-synaptic receptor; involved in nerve transduction events related to long-term potentiation (LTP) and long-term depression (LTD); increases NMDA receptor activity |

| mGluR2 | GRM2 | metabotropic, group II family | GPCR coupled to Gi-type G-protein; primarily a presynaptic receptor; involved in synaptic plasticity by exerting transient suppression of synaptic transmission occurring in response to receptor activation, induces persistent long-term depression (LTD), and mediates inhibition of long-term potentiation (LTP) |

| mGluR3 | GRM3 | metabotropic, group II family | GPCR coupled to Gi-type G-protein; primarily a presynaptic receptor; polymorphisms in GRM3 gene associated with psychosis and schizophrenia; modulates expression of glutamate transporters; affects NMDA receptor activity |

| mGluR4 | GRM4 | metabotropic, group III family | GPCR coupled to Gi-type G-protein; primarily a presynaptic receptor; depresses excitatory transmission by preventing glutamate release |

| mGluR5 | GRM5 | metabotropic, group I family | GPCR coupled to Gq-type G-protein; primarily a postsynaptic receptor; critical receptor involved in inhibitory learning processes such as drug-related self-administration learning; reduced signaling from this receptor can reverse fragile X phenotypes |

| mGluR6 | GRM6 | metabotropic, group III family | GPCR coupled to Gi-type G-protein; primarily a presynaptic receptor; involved in a photoreceptor-independent form of light adaptation within the retina; found on the photoreceptor–On bipolar cell synapse |

| mGluR7 | GRM7 | metabotropic, group III family | GPCR coupled to Gi-type G-protein; most widely distributed pre-synaptic mGluR; found at a wide range of synapses postulated to be critical for both normal CNS function and several human disorders; is a key regulator in shaping synaptic responses at glutamatergic synapses as well as in regulating critical aspects of inhibitory GABAergic transmission |

| mGluR8 | GRM8 | metabotropic, group III family | GPCR coupled to Gi-type G-protein; primarily a pre-synaptic receptor; involved in anxiety by depressing excitatory synaptic transmission in the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST) |

| GluA1 (GluR1) | GRIA1 | ionotropic: AMPA | responsible for the bulk of fast excitatory synaptic transmission throughout the CNS |

| GluA2 (GluR2) | GRIA2 | ionotropic, AMPA | controls the Ca 2+ permeability of the AMPA receptor channels; RNA editing controls the permeability by altering a single amino acid (the Q/R site) in the second transmembrane domain (TMII) of the protein, if unedited the Q residue allows Ca 2+ permeability whereas the edited amino acid (R) does not; almost all the CNS GluA2 is edited |

| GluA3 (GluR3) | GRIA3 | ionotropic, AMPA | responsible for the bulk of fast excitatory synaptic transmission throughout the CNS |

| GluA4 (GluR4) | GRIA4 | ionotropic, AMPA | responsible for the bulk of fast excitatory synaptic transmission throughout the CNS |

| GluK1 (GluR5) | GRIK1 | ionotropic, Kainate | three splice variants |

| GluK2 (GluR6) | GRIK2 | ionotropic, Kainate | two splice variants |

| GluK3 (GluR7) | GRIK3 | ionotropic, Kainate | |

| GluK4 (KA1) | GRIK4 | ionotropic, Kainate | expressed almost exclusively in the hippocampus |

| GluK5 (KA2) | GRIK5 | ionotropic, Kainate | protein retained within the ER unless assembled into a complex with either GluK1, GluK2, or GluK3 |

| GluN1 (NR1, NMDAR1) | GRIN1 | ionotropic, NMDA | functional NMDA receptors requires simultaneous binding of both glutamate and glycine; GluN1 provides the glycine-binding site as does the GluN3 subunits; receptors function as modulators of synaptic response and are involved in co-incidence detection (bidirectional current flow at a synapse) |

| GluN2A (NR2A, NMDAR2A) | GRIN2A | ionotropic, NMDA | functional NMDA receptors requires simultaneous binding of both glutamate and glycine; the GluN2 subunits provide the glutamate-binding sites; receptors function as modulators of synaptic response and are involved in co-incidence detection (bidirectional current flow at a synapse) |

| GluN2B (NR2B, NMDAR2B) | GRIN2B | ionotropic, NMDA | functional NMDA receptors requires simultaneous binding of both glutamate and glycine; the GluN2 subunits provide the glutamate-binding sites; receptors function as modulators of synaptic response and are involved in co-incidence detection (bidirectional current flow at a synapse) |

| GluN2C (NR2C, NMDAR2C) | GRIN2C | ionotropic, NMDA | functional NMDA receptors requires simultaneous binding of both glutamate and glycine; the GluN2 subunits provide the glutamate-binding sites; receptors function as modulators of synaptic response and are involved in co-incidence detection (bidirectional current flow at a synapse) |

| GluN2D (NR2D, NMDAR2D) | GRIN2D | ionotropic, NMDA | functional NMDA receptors requires simultaneous binding of both glutamate and glycine; the GluN2 subunits provide the glutamate-binding sites; receptors function as modulators of synaptic response and are involved in co-incidence detection (bidirectional current flow at a synapse) |

| GluN3A (NR3A, NMDAR3A) | GRIN3A | ionotropic, NMDA | functional NMDA receptors requires simultaneous binding of both glutamate and glycine; GluN3 subunits provide the glycine-binding sites as does the GluN1 subunit; receptors function as modulators of synaptic response and are involved in co-incidence detection (bidirectional current flow at a synapse) |

| GluN3B (NR3B, NMDAR3B) | GRIN3B | ionotropic, NMDA | functional NMDA receptors requires simultaneous binding of both glutamate and glycine; GluN3 subunits provide the glycine-binding sites as does the GluN1 subunit; receptors function as modulators of synaptic response and are involved in co-incidence detection (bidirectional current flow at a synapse) |

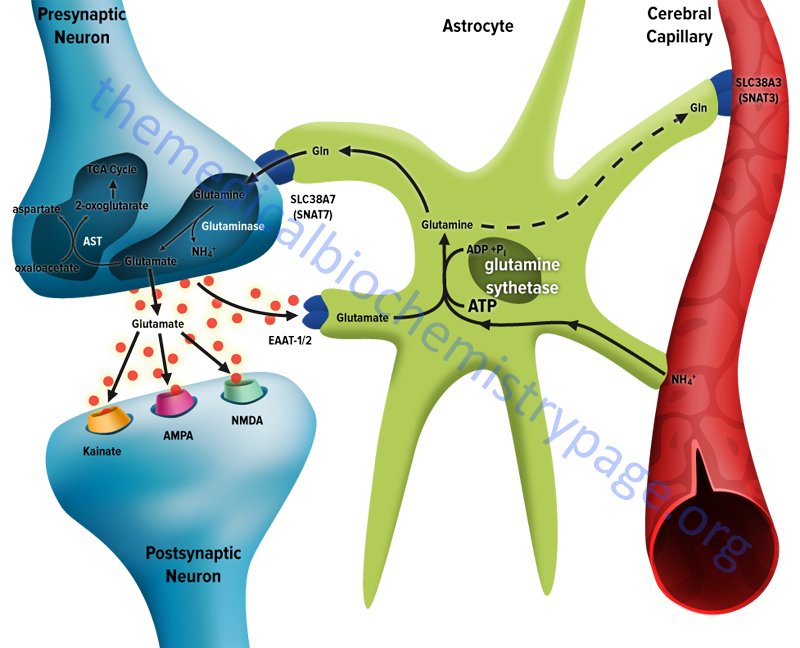

Within the CNS there is an interaction between the cerebral blood flow, neurons, and the protective astrocytes that regulates the metabolism of glutamate, glutamine, and ammonia. This process is referred to as the glutamate-glutamine cycle and it is a critical metabolic process central to overall brain glutamate metabolism. Using presynaptic neurons as the starting point, the cycle begins with the release of glutamate from presynaptic secretory vesicles in response to the propagation of a nerve impulse along the axon. The release of glutamate is a Ca 2+ -dependent process that involves fusion of glutamate containing presynaptic vesicles with the neuronal membrane.

Following release of the glutamate into the synapse it must be rapidly removed to prevent over excitation of the postsynaptic neurons. Synaptic glutamate is removed by three distinct process. It can be taken up into the postsynaptic cell, it can undergo reuptake into the presynaptic cell from which it was released or it can be taken up by a third non-neuronal cell, namely astrocytes. Postsynaptic neurons remove little glutamate from the synapse and although there is active reuptake into presynaptic neurons the latter process is less important than transport into astrocytes.

The membrane potential of astrocytes is much lower than that of neuronal membranes and this favors the uptake of glutamate by the astrocyte. Glutamate uptake by astrocytes is mediated by Na + -independent and Na + -dependent systems. The Na + -dependent systems have high affinity for glutamate and are the predominant glutamate uptake mechanism in the central nervous system. There are two distinct astrocytic Na + -dependent glutamate transporters identified as EAAT1 (for Excitatory Amino Acid Transporter 1; also called GLAST) and EAAT2 (also called GLT-1).

Following uptake of glutamate, astrocytes have the ability to dispose of the amino acid via export into the blood though capillaries that contact the foot processes of the astrocytes. The problem with glutamate disposal via this mechanism is that it would eventually result in a net loss of carbon and nitrogen from the CNS. In fact, the outcome of astrocytic glutamate uptake is its conversion to glutamine. Glutamine thus serves as a “reservoir” for glutamate but in the form of a non-neuroactive compound. Release of glutamine from astrocytes allows neurons to derive glutamate from this parent compound. Astrocytes readily convert glutamate to glutamine via the glutamine synthetase catalyzed reaction as this microsomal enzyme is abundant in these cells. Indeed, histochemical data demonstrate that the glia are essentially the only cells of the CNS that carry out the glutamine synthetase reaction. The ammonia that is used to generate glutamine is derived from either the blood or from metabolic processes occurring in the brain.

Like the uptake of glutamate by astrocytes, neuronal glutamine uptake proceeds via both Na + -dependent and Na + -independent mechanisms. The major glutamine transporter in both excitatory and inhibitory neurons is the system N neutral amino acid transporter SNAT7 which is encoded by the SLC38A7 gene. The predominant metabolic fate of the glutamine taken up by neurons is hydrolysis to glutamate and ammonia via the action of the mitochondrial form of glutaminase encoded by the GLS2 gene. This form of glutaminase is referred to as phosphate-dependent glutaminase (PAG). The inorganic phosphate (Pi) necessary for this reaction is primarily derived from the hydrolysis of ATP and its function is to lower the KM of the enzyme for glutamine. During depolarization there is a sudden increase in energy consumption. The hydrolysis of ATP to ADP and Pi thus favors the concomitant hydrolysis of glutamine to glutamate via the resulting increased Pi.

Because there is a need to replenish the ATP lost during neuronal depolarization, metabolic reactions that generate ATP must increase. It has been found that not all neuronal glutamate derived from glutamine is utilized to replenish the neurotransmitter pool. A portion of the glutamate can be oxidized within the nerve cells following transamination. The principal transamination reaction involves aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and yields α-ketoglutarate (2-oxoglutarate) which is a substrate in the TCA cycle. Glutamine, therefore, is not simply a precursor to neuronal glutamate but a potential fuel, which, like glucose, supports neuronal energy requirements.

Glutamate, released as a neurotransmitter, is taken up by astrocytes, converted to glutamine, released back to neurons where it is then converted back to glutamate represents the complete glutamate-glutamine cycle. The significance of this cycle to brain glutamate handling is that it promotes several critical processes of CNS function. Glutamate is rapidly removed from the synapse by astrocytic uptake thereby preventing over-excitation of the postsynaptic neuron. Within the astrocyte glutamate is converted to glutamine which is, in effect, a non-neuroactive compound that can be transported back to the neurons. The uptake of glutamine by neurons provides a mechanism for the regeneration of glutamate which is augmented by the generation of Pi as a result of ATP consumption during depolarization. Since the neurons also need to regenerate the lost ATP, the glutamate can serve as a carbon skeleton for oxidation in the TCA cycle. Lastly, but significantly, the incorporation of ammonia into glutamate in the astrocyte serves as a mechanism to buffer brain ammonia.

Glycine, as an amino acid found in proteins, is critical to the functions of several different classes of protein, particularly those of the extracellular matrix. However, glycine as a free amino acid also functions as a highly important neurotransmitter within the central nervous system, CNS. Glycine and GABA are the major inhibitory neurotransmitters in the CNS, whereas, glutamate is the major excitatory neurotransmitter. In conjunction with glutamate, glycine can also function in an excitatory capacity as a co-agonist acting on the NMDA subtype of glutamate receptors (see section above). The receptors to which glycine binds were originally identified by their sensitivity to the alkaloid strychnine. Strychnine-sensitive glycine receptors (GlyR) mediate the synaptic inhibition exerted in response to glycine binding. Glycinergic synapses mediate fast inhibitory neurotransmission within the spinal cord, brainstem, and caudal brain. The effects of glycine exert control over a variety of motor and sensory functions, including vision and audition. The GlyR are members of the ionotropic family of ligand-gated ion channels. The binding of glycine leads to the opening of the GlyR integral anion channel, and the resulting influx of Cl – ions hyperpolarizes the postsynaptic cell, thereby inhibiting neuronal firing.

Cellular uptake of glycine, particularly within neurons in the central nervous system (CNS), is regulated by the presence of specific glycine transporters identified as GlyT. There are two subtypes of GlyT identified as GlyT1 and GlyT2. Both glycine transporters are members of the solute carrier family of membrane transporters. The GlyT1 protein is encoded by the SLC6A9 gene and the GlyT2 protein is encoded by the SLC6A5 gene. The tissue distribution and function of the two glycine transporters are distinct. GlyT1 is predominantly expressed in glutamatergic neurons where it functions in the regulation of glycine levels in the vicinity of the NMDA-type glutamate receptors. GlyT2 is predominantly expressed in glycinergic neurons where it functions to regulate inhibitory glycinergic neurotransmission by decreasing synaptic glycine concentrations after presynaptic release. A form of inherited hyperekplexia of presynaptic origin (HKPX3) results from mutations in the SLC6A5 (GlyT2) gene.

Impaired glutamatergic neurotransmission via the NMDA receptors has been associated with the symptoms of schizophrenia and the associated cognitive deficit. Pharmacologic inhibitors of GlyT1 have some utility to improve impaired NMDA receptor function in psychosis by increasing synaptic glycine concentrations. These transport inhibitors function by increasing extrasynaptic glycine concentrations via inhibition of its neuronal or glial reuptake processes. When used in combination with other antipsychotic medications, GlyT1 inhibitors have been shown to be capable of restoring disturbed glutamatergic-GABAergic-dopaminergic balance in psychosis.

The receptors to which glycine binds (GlyR) are members of the group I ligand-gated ion channel (LGIC) class of receptors. The LGIC receptors are members of the Cys loop receptor family that also includes the nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChR), the serotonin type 3 receptor (5-HT3), and the GABAA receptors (GABAAR). The GlyR are composed of three different proteins, two of which constitute the actual receptor and a third protein that serves a scaffolding function.

The receptor subunits are referred to as GlyRα and GlyRβ. These subunits are tightly bound to a cytosolic scaffolding protein identified as gephyrin that is encoded by the GPHN gene. Gephyrin is tightly bound to the GlyRβ subunit. In addition to its role in GlyR function, gephryin functions to regulate the activity of the GABAA receptor and it is required for molybdenum cofactor biosynthesis. Functional GlyR are heteropentameric proteins similar to the organization of the nAChR found in skeletal muscle. The typical subunit composition of the heteropentameric GlyR is (GlyRα)2(GlyRβ)3.

Humans express four GlyR genes encoding α subunits (GLRA1–GLRA4) and a single GlyR gene encoding the β subunit (GLRB). All GlyRα subunits display high amino acid sequence identity and form functional homomeric glycine-gated channels. The GlyRα subunits possess critical determinants of ligand binding.

The GLRA1 gene is located on chromosome 5q32 and is composed of 10 exons that generate three alternatively spliced mRNAs. Glycine receptors that contain the GlyRα1 subunit represent the predominant form of the α-subunit in adult glycine receptors. Several mutations in the GLRA1 gene have been shown to be associated with the startle disease known as hereditary hyperekplexia type 1, HKPX1. The hallmark symptoms of HKPX1 are an exaggerated startle response to auditory or tactile stimuli and, particularly in neonates, transient muscle rigidity referred to as “stiff baby syndrome”.

The GLRA2 gene is located on the X chromosome (Xp22.2) and is composed of 13 exons that generate four alternatively spliced mRNAs. Two of the splice variant GLRA2 mRNAs encode the same protein, thus, the four variant mRNAs generate three different GLRA2 proteins.

The GLRA3 gene is located on chromosome 4q34.1 and is composed of 13 exons that generate two alternatively spliced mRNAs. In addition to alternative splicing, the GLRA3 mRNA is subject to editing that results in the substitution of a Pro residue for a Leu residue at amino acid 185 in the extracellular domain. This version of the GlyRα3 protein confers an increased agonist affinity to GlyRα3-containing glycine receptors. The GlyRα3-containing GlyRs are involved in the pathways of nociception (pain sensation) within the spinal cord. Specific spinal cord neurons (in laminae I and II) mediate pain sensation in response to the inflammatory mediator, prostaglandin E2 (PGE2). When PGE2 binds to its receptor in these neurons (the EP2 receptor), PKA is activated which then phosphorylates the GlyRα3 protein in the glycine receptor resulting in down-regulation of glycine stimulated inhibitory circuits in these neurons. The analgesic effects of cannabinoids and endocannabinoids involves the modulation of GlyRα3-containing glycine receptors. Thus, it is postulated that GlyRα3 represents a potentially useful target for the pharmacologic intervention in chronic pain syndromes.

The GLRA4 gene is located on the X chromosome (Xq22.2) on the other arm relative to the position of the GLRA2 gene. The GLRA4 gene is composed of 9 exons that generate two alternatively spliced mRNAs.

The GlyRβ gene is located on chromosome 4q31.3 and is composed of 12 exons that generate three alternatively spliced mRNAs that encode two distinct GlyRβ isoforms. Unlike the GlyRα subunits which can form a functional glycine-gated ion channel, the GlyRβ protein cannot form a functional glycine receptor on its own. The role of the GlyRβ subunit is to regulate agonist binding and intracellular trafficking and synaptic clustering of post-synaptic GlyR. Mutations in the GLRB gene are associated with another form of hyperekplexia identified as HKPX2.

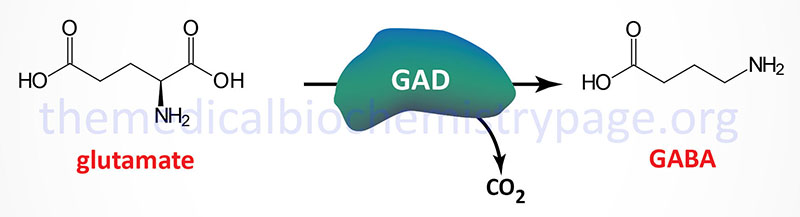

Several amino acids have distinct excitatory or inhibitory effects upon the nervous system. The amino acid derivative, γ-aminobutyrate (GABA; also called 4-aminobutyrate) is a major inhibitor of presynaptic transmission in the CNS, and also in the retina. Neurons that secrete GABA are termed GABAergic. GABA cannot cross the blood-brain-barrier and as such must be synthesized within neurons in the CNS. The synthesis of GABA in the brain occurs via a metabolic pathway referred to as the GABA shunt.

Glucose is the principal precursor for GABA production via its conversion to 2-oxoglutarate (α-ketoglutarate) in the TCA cycle. Within the context of the GABA shunt, GABA is synthesized in the cytosol via the reaction described in the next section.

GABA is transported into the mitochondria and converted to succinic semialdehyde through the action of 4-aminobutyrate aminotransferase (commonly called GABA transaminase). GABA transaminase uses pyruvate as the amino group acceptor converting pyruvate to alanine. Succinic semialdehyde is then oxidized to succinate by the NAD + -dependent enzyme, succinic semialdehyde dehydrogenase.

The succinate can then enter the TCA cycle and be converted to 2-oxoglutarate which can, in turn be converted to glutamate through the action of the mitochondrial glutamate dehydrogenase encoded by the GLUD1 gene. The glutamate is transported out of the mitochondria and can again serve as the substrate for GABA synthesis.

GABA transaminase is encoded by the ABAT gene which is located on chromosome 16p13.2 and is composed of 23 exons that generate 20 alternatively spliced mRNAs that collectively encode 11 different protein isoforms.

Succinic semialdehyde dehydrogenase is encoded by the ALDH5A1 (aldehyde dehydrogenase 5 family member A1) gene which is located on chromosome 6p22.3 and is composed of 11 exons that generate three alternatively spliced mRNAs, each of which encode a distinct protein isoforms.

Glutamate decarboxylase (GAD) catalyzes the decarboxylation of glutamic acid to form GABA. There are two GAD genes in humans identified as GAD1 and GAD2. The major GAD isoforms produced by these two genes are identified as GAD67 (GAD1 gene) and GAD65 (GAD2 gene) which is reflective of their molecular weights. Both the GAD1 and GAD2 genes are expressed in the brain and GAD2 expression also occurs in the pancreas but at significantly lower levels than in the brain.

The GAD1 gene is located on chromosome 2q31.1 and is composed of 21 exons that generates two alternatively spliced mRNAs. The major GAD1 encoded mRNA generates a protein of 591 amino acids (67 kDa: GAD67) while the minor mRNA generates a protein of 224 amino acids (25 kDa: GAD25). The GAD2 gene is located on chromosome 10p12.1 and is composed of 16 exons that generate two alternatively spliced mRNAs, both of which encode the same protein of 585 amino acid (65 kDa: GAD65).

The activity of GAD requires pyridoxal phosphate (PLP) as a cofactor. PLP is generated from the B6 vitamins (pyridoxine, pyridoxal, and pyridoxamine) through the action of pyridoxal kinase. Pyridoxal kinase itself requires zinc for activation. A deficiency in zinc or defects in pyridoxal kinase can lead to seizure disorders, particularly in seizure-prone pre-eclamptic (hypertensive condition in late pregnancy) patients.

The presence of anti-GAD antibodies (both anti-GAD65 and anti-GAD67) is a strong predictor of the future development of type 1 diabetes in high-risk populations.

GABA exerts its effects by binding to two distinct receptor subtypes. The GABA-A (GABAA) receptors are members of the ionotropic receptors, specifically the Cys-loop subfamily of ligand-gated ion channels that includes the nicotinic ACh receptors (nAChR), glycine receptors (GlyR), and the 5-HT3 (serotonin) receptors. The GABA-B (GABAB) receptors belong to the class C family of metabotropic G-protein coupled receptors (GPCR). The GABA-A receptors are members of the ionotropic receptor family and are chloride channels that, in response to GABA binding, increase chloride influx into the GABAergic neuron. The GABA-B receptors are coupled to a G-protein that activates an associated potassium channel that when activated by GABA leads to potassium efflux from the cell. The anxiolytic drugs of the benzodiazepine family exert their soothing effects by potentiating the responses of GABA-A receptors to GABA binding.

Functional GABA-A receptors are generated by the combination of a wide array of different subunits. A total of 19 GABA-A receptor subunit genes have been identified in humans that code for α (alpha), β (beta), γ (gamma), δ (delta), ε (epsilon), π (pi), θ (theta), and ρ (rho). The overall diversity of GABA-A receptors is further increased as several of these genes undergo alternative splicing. The complexity of the diverse array of molecular compositions of the GABA-A receptors has important functional and clinical consequences as they determine the properties and pharmacological modulations of a given receptor complex. In addition, zinc ions are known to regulate GABA-A receptor activity via inhibition of the receptor through an allosteric mechanism that is critically dependent on the receptor subunit composition. The GABRG3 (γ3 subunit gene) encoded protein is critical to this zinc-mediated regulation. Although the minimal requirement to produce a functional GABA-gated ion channel is the inclusion of both α and β subunits, the most common type in the brain is a heteropentameric complex composed of two α subunits, two β subunits, and a γ subunit (α2β2γ). The GABA-A receptors bind two molecules of GABA and in the heteropentameric receptors this binding site is created by the interface between the α and β subunits.

The GABA-Aρ subunits do not form heteromeric complexes with other GABA-A receptor subunits but only form homomeric receptor complexes. The GABA-Aρ receptors were formerly referred to as the GABA-C receptors.

The anxiolytic/sedative effects of the barbiturates and benzodiazepines are exerted via their binding to subunits of the GABA-A receptors. Benzodiazepines bind to a site on the GABA-A receptor created by the association of the gamma (γ) subunit and one of the alpha (α) subunits. There are two distinct subtypes of benzodiazepine receptors termed BZ1 (BZ1) and BZ2 (BZ2). The BZ1 receptor is formed by the interaction of γ and α1 subunits, whereas the BZ2 receptors is formed by the interaction of the γ and α2, α3 or α5 subunits. The receptor for the barbiturates is the beta (β) subunit of the GABA-A receptor. When benzodiazepines bind to the GABA-A receptor they potentiate the actions of GABA and require the presence of GABA in order for activation of the ion channel. Barbiturates can induce GABA-A channel opening in the absence of GABA when administered at high dose and as a result they can be lethal due to the level of CNS suppression. The potential for lethal toxicity of a benzodiazepine requires an extremely large dose. This difference in toxicity between barbiturates and benzodiazepines is the major reason barbiturates are not often used clinically any longer.

Under physiological conditions the binding of GABA to any of the GABA-A receptors leads to membrane hyperpolarization and a reduction of action potential firing. However, studies have also demonstrated the GABA-A activation can result in membrane reversal potential that is close to, or even at a more depolarized potential than the resting membrane potential at a synapse. This results in a membrane depolarization referred to as shunting inhibition. Shunting inhibition is also called divisive inhibition and defines a form of post-synaptic potential inhibition. The term shunting is used because the synaptic conductance short-circuits currents that are generated at adjacent excitatory synapses. If a shunting inhibitory synapse is activated, the amplitude of subsequent excitatory postsynaptic potentials (EPSPs) is reduced.

The major effect of GABA-A receptor activation is reduced dendritic excitatory glutamatergic responses as a consequence of a local increase in conductance across the plasma membrane. In addition to shunting inhibition, the polarity of GABA-A receptor-mediated responses can change during different physiological or pathological conditions. For example, GABA triggers excitation during the day and inhibition during the night within neural circuits of the suprachiasmatic nucleus. Also, the repeated activation of GABA-A receptors can lead to a switch from a hyperpolarizing to depolarizing direction and can, thus, enhance cell firing. The activation of GABA-A receptors results in both phasic inhibitory postsynaptic currents (IPSCs) and tonic currents. The GABA-A-induced tonic current result from GABA acting on extrasynaptic receptors composed of a different subunit composition and therefore, different pharmacological activity compared with the synaptic receptors.

| Receptor Subunit | Gene Symbol | Functions / Comments |

| GABA-A alpha 1 (α1) | GABRA1 | GABRA1 protein is phosphorylated in a glycolysis-dependent reaction involving a kinase activity associated with the enzyme glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), GAPDH-mediated phosphorylation maintains functionality of the protein; this process implicates a link between regional cerebral glucose metabolism and GABAergic currents since the mechanism depends on locally produced glycolytic ATP and GAPDH activity; cortical tissue isolated from epileptic patients contains GABRA1 subunits in a reduced phosphorylation state compared to tissue from non-epileptic individuals; mutations in the GABRA1 gene associated with susceptibility to juvenile myoclonic epilepsy |

| GABA-A alpha 2 (α2) | GABRA2 | polymorphisms in the GABRA2 gene associated with susceptibility to alcohol dependence; pharmacologic-specific activation of the GABA-A α2 subunit is highly effective against inflammatory and neuropathic pain without sedation typical of benzodiazepine activation of the α1 subunit |

| GABA-A alpha 3 (α3) | GABRA3 | similar to effects at the α2 subunit, pharmacologic-specific activation of the GABA-A α3 subunit is highly effective against inflammatory and neuropathic pain without sedation typical of benzodiazepine activation of the α1 subunit |

| GABA-A alpha 4 (α4) | GABRA4 | pentameric GABA-A receptors that contain the α4 subunit are insensitive to benzodiazepines; shunting inhibition involving GABA-A receptor complexes that contain the α4 subunit reduces NMDA receptor activation leading to impaired long-term potentiation, LTP |

| GABA-A alpha 5 (α5) | GABRA5 | variable numbers of a partial duplication in the GABRA5 gene are found in different individuals; the GABRA5 gene is located within the chromosome 15 imprinted region found deleted in Prader-Willi and Angelman syndromes; the duplication number is higher in individuals with cytogenetically detectable deletions in the 15q region |

| GABA-A alpha 6 (α6) | GABRA6 | cerebellar motor control is likely to be a distinct behavioral function associated with GABA-A receptors that contain the α6 subunit; disruption in expression of the GABRA6 gene leads to an associated loss of expression from the GABRD gene |

| GABA-A beta 1 (β1) | GABRB1 | |

| GABA-A beta 2 (β2) | GABRB2 | |

| GABA-A beta 3 (β3) | GABRB3 | the GABRA3 gene is located within the chromosome 15 imprinted region found deleted in Prader-Willi and Angelman syndromes; deletion of GABRB3 is found in both disorders and it is, therefore, suggested that loss of the β3 subunit plays a role in the pathogenesis of these syndromes |

| GABA-A gamma 1 (γ1) | GABRG1 | both the γ1 and γ2 subunits are important in the effects of the benzodiazepines on GABA-A receptor function; |

| GABA-A gamma 2 (γ2) | GABRG2 | both the γ1 and γ2 subunits are important in the effects of the benzodiazepines on GABA-A receptor function; polymorphisms in the GABRG2 gene are associated with susceptibility to epilepsy and febrile seizures; presence of the γ2 subunit results in a low sensitivity of GABA-A receptors to allosteric regulation by zinc ion |

| GABA-A gamma 3 (γ3) | GABRG3 | the γ3 subunit is critical to the allosteric regulation of GABA-A receptors by zinc ions whereas presence of the γ2 subunit results in a low sensitivity to zinc ion regulation |

| GABA-A delta (δ) | GABRD | polymorphisms in the GABRD gene are associated with susceptibility to epilepsy and febrile seizures; three variants of the GABRD protein are produced in the brain identified as GABRD-1A, -1B, and -1C; the δ subunit is involved in the tonic (continuous) currents elicited by GABA-A receptors which modifies the spatial and temporal integration of excitatory neurotransmission |

| GABA-A epsilon (ε) | GABRE | alternative splicing of the GABRE mRNA occurs at several positions depending upon the tissue of expression |

| GABA-A pi (π) | GABRP | expressed at highest levels in the uterus; presence of the π subunit in pentameric GABA-A receptors modifies the receptor sensitivity to steroidogenic compounds |

| GABA-A theta (θ) | GABRQ | |

| GABA-A rho 1 (ρ1) | GABRR1 | protein contains a chloride-sensitive anion channel |

| GABA-A rho 2 (ρ2) | GABRR2 | |

| GABA-A rho 3 (ρ3) | GABRR3 |

GABA also acts on GABA-B receptors that are members of the GPCR family of receptors. There are two GABA-B receptors subunits identified as GABA-B1 (GABAB1) and GABA-B2 (GABAB2). These two subunits heterodimerize to form the functional receptor that can be found on both pre- and post-synaptic membranes. Neither receptor subunit is functional as a GABA receptor independently.

The GABA-B receptors are coupled to G-proteins of the Gi type. The G-protein is linked to potassium channels (GIRK or Kir3) and activation of the G-protein results in increased conductance of the associated channel. GABA-B receptor activation on post-synaptic membranes generally leads to activation of the inwardly rectifying potassium channels which underlies the late phase of inhibitory postsynaptic potentials (IPSP). Activation of pre-synaptic GABA-B receptors decreases neurotransmitter release by inhibiting voltage-activated Ca 2+ channels of the N or P/Q types.

Activation of GABA-B receptors also modulates the production of cAMP. This function leads to a wide range of actions on ion channels as well as other proteins that are targets of PKA. The cAMP modulation by GABA-B receptors effects modulation of both neuronal and synaptic functions.

The anxiolytic/sedative effects of the barbiturates and benzodiazepines are exerted via their binding to subunits of the GABA-A receptors. Benzodiazepines bind to a site on the GABA-A receptor created by the association of the gamma (γ) subunit and one of the alpha (α) subunits.

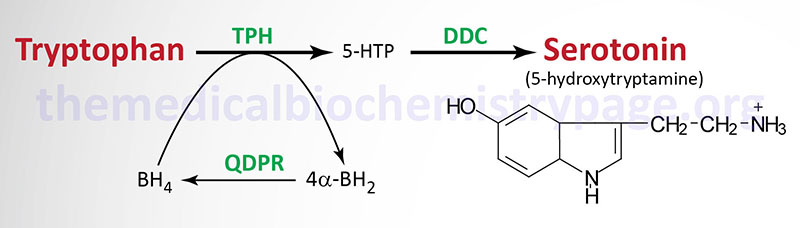

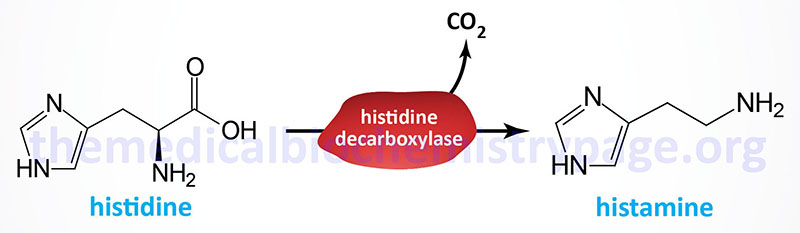

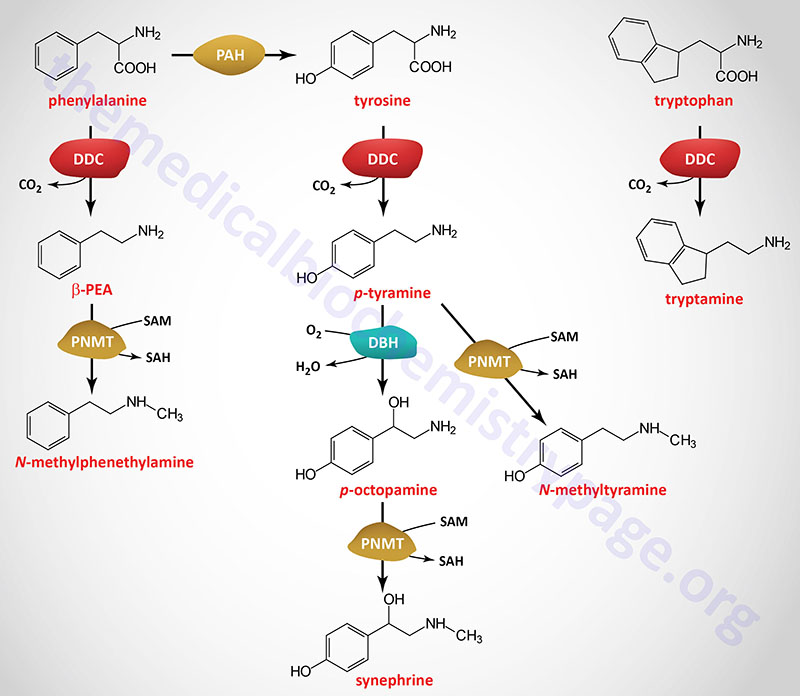

There are two distinct subtypes of benzodiazepine receptors termed BZ1 (BZ1) and BZ2 (BZ2). The BZ1 receptor is formed by the interaction of γ and α1 subunits, whereas the BZ2 receptors is formed by the interaction of the γ and α2, α3 or α5 subunits.